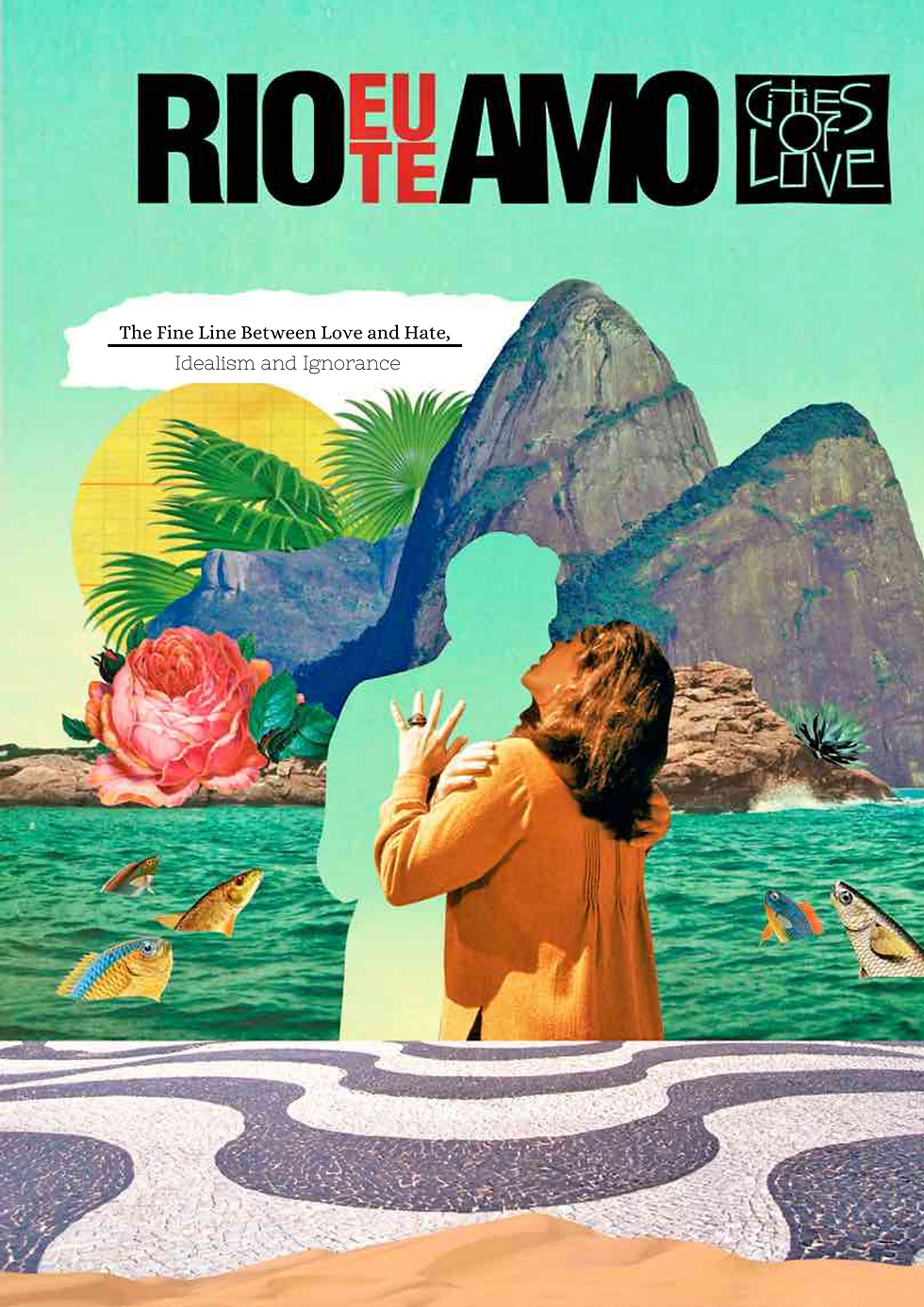

Rio de Janeiro Remains Radiant: Gringos Grappling with Gems and Gaps in 'Rio, I Love You'

- Sofia R. Willcox

- Jul 22, 2024

- 3 min read

Heading into the week of the start of an international sports tournament such as the Olympics, it is almost unlikely to have a throwback from 10 years ago in 2014. The World Cup took place in my home country, and two years later, the Olympic Games were held in Rio de Janeiro, just a bridge away from home. “Fuleco,” did not scare away the fans. Vuvuzelas, passionate fans and fireworks provided the main soundtrack.

Flash forward ten years to a homesick night in England. While zapping around the streaming platforms, I discovered a hidden gem: “Rio, I Love You” (various directors, 2014). Emmanuel Benbihy, the creator of the Cities of Love franchise, created and produced this anthology film, which stars a diverse cast and filmmakers. “Rio, I Love You” is the fourth instalment in the series. The movie fit like a glove to the event, almost like a promotion to boost tourism, as 704,483 visitors per year were not enough (plus millions in population terms). Without further ado, let’s delve into the representation of Rio de Janeiro in “Rio, I Love You.”

On the one hand, “Rio, I Love You” does justice to Brazilian culture. Its soundtrack draws from our melting pot, featuring varied names like Gilberto Gil, Luiz Gonzaga, Bebel Gilberto, Elis Regina, Tom Jobim, and Cartola. Not only that, but the film also boasts a heavyweight cast, including Fernanda Montenegro, Regina Casé, Rodrigo Santoro, and Wagner Moura. Brazilian talent is evident behind the cameras too, with directors like Carlos Saldanha (Rio), José Padilha (Elite Squad), Andrucha Waddington (The House of Sand), and Fernando Meirelles (City of God).

The film honours the natural beauty and charm of Rio de Janeiro with numerous aerial shots of the city and its well-known landmarks during golden hour, as well as lesser-known places in various neighbourhoods. It showcases everything from urban areas to natural landscapes, from wealthy districts to suburban ghettos. The passionate people within' many love relationships types.

However, “Rio, I Love You” holds many problematic elements. The film portrays Brazilian women through sexualization and objectification, making them victims of the male gaze from both male characters and directors. There is a gringo’s denial of Brazilian Portuguese, with characters speaking Spanish or Italian instead of Brazil’s multicultural mother tongue. The casting of non-disabled actors to play characters with disabilities is another issue. Additionally, the film lacks diversity; Brazil is a nation of miscegenation, yet even the love stories are heteronormative. Fernanda Montenegro's portrayal of a homeless person as a happy choice is troubling in a country where socio-economic inequality reigns.

“Rio, I Love You” has two highlights. The narrative is a high point. The stories are independent of one another, though simultaneous. Sometimes, the characters connect, revealing different facets of themselves. One powerful monologue from Gui (Wagner Moura), delivered while paragliding, states: “The city is a lie. The police are killing people. When it rains, it floods the whole place; everyone dies. The children are without school. The higher social classes don’t care about social problems. I’m leaving. Wonderful city is a fucking joke. Open arms are a lie.” The scene shot from an aerial angle, which symbolically represents monetary power and privilege. Additionally, it serves as social commentary that resonates with many Brazilians. Though, this advantage point might connect with gringos.

This perspective contrasts with other stories in the film, where the film portrays Rio de Janeiro as a paradise or even an aphrodisiac for foreigners, who maintain a superficial view of the country. Still using Pelé as a primary football reference in the 2010s. Displaying complete ignorance with depictions of sharks in the Sugarloaf Mountains or vampires in Vidigal. It highlights their ethnocentrism, exoticism, and fear of the unknown.

Brazil is a victim of the street dog complex. Brazilian writer Nelson Rodrigues coined the term to refer to the trauma following the 1950 World Cup, when Uruguay’s national team defeated the Brazilian football team in the final match. He defined it as “the inferiority in which Brazilians put themselves, voluntarily, in comparison to the rest of the world. Brazilians are the backward Narcissus, who spit in their own image. Here is the truth: we can't find personal or historical pretexts for self-esteem.”

This relates to 'Rio, I Love You,' as the film portrays Brazil as a street dog—unwanted yet exploited. However, we Brazilians are aware of the layers this nationality carries. We are citizens on paper, mere numbers in statistics, subject matter in the news, but subjects who do not matter in society. We are ghosts haunting and hiding. There are many hidden gems within us, many stories to (re)tell, and it is up to us to do it. No one else will ever know them unless we make a move.

Comments